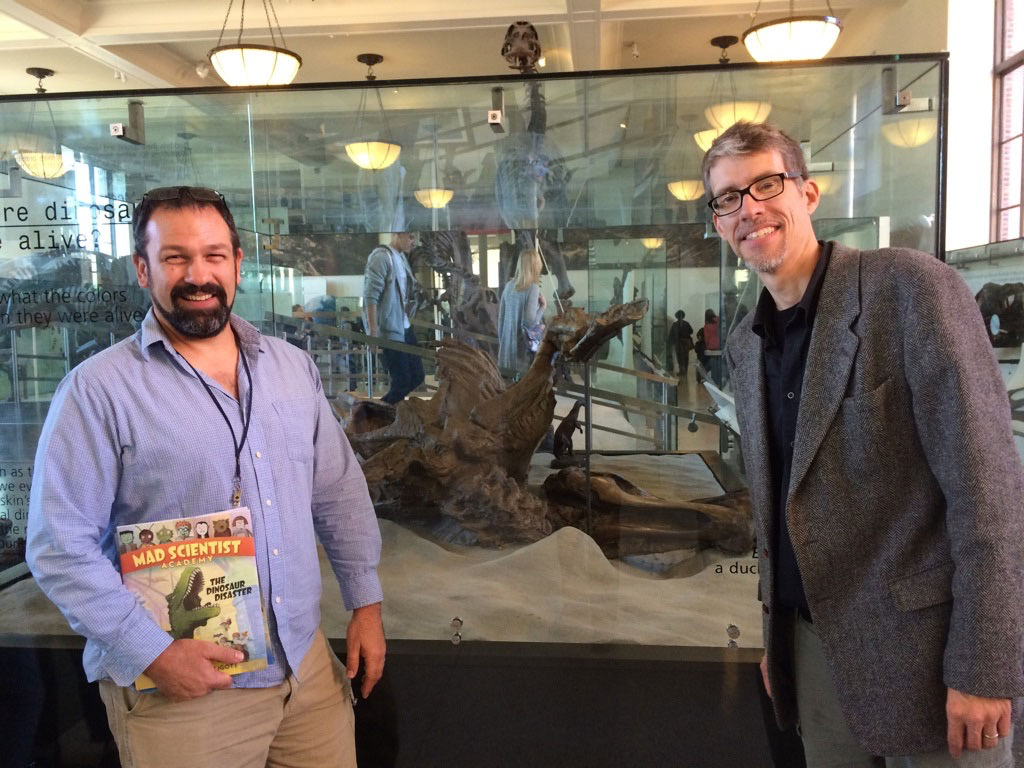

One of the best things about working on the Mad Scientist Academy books is that I get to meet real scientists as part of my research. When I was writing The Dinosaur Disaster, I got to work with a real-life dinosaur expert, Carl Mehling, a paleontologist and Senior Scientific Assistant at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. He helped me make sure all of my dinosaur facts were correct.

Recently, I took a trip down to New York to meet him in person and ask him about his job. I learned all about what he does and some of his favorite discoveries. You can read all about it in our interview below.

Mr. Mehling, you’re a paleontologist. What is that, exactly?

Basically, it’s someone who studies fossils. I study fossils. I write about them. I am obsessed with them, and I collect all I can around the world. I really enjoy that. I think if somebody lives, breathes, and thinks fossils, they’re a paleontologist.

Where did your interest in dinosaurs come from?

I got hooked on dinosaurs really early on, like a lot of kids did. As I got older, I was interested in all kinds of things to do with studying animals. In 1987 the Museum of Natural History had a special exhibit on dinosaurs. There were so many new discoveries and I got SUPER excited about paleontology again.

How did you end up working at the museum?

I started volunteering in the paleontology department. I learned about caring for the fossils, organizing them, and removing them from the rock. It was so interesting, and I realized that I was going to try to get the job that I currently have.

I bounced around the museum in other jobs, trying to be involved, always with my eye on the “paleontologist librarian” job. The woman that had the position that I wanted had worked in the museum for almost 40 years. When she retired, I was in the perfect place to get the job.

I got really, really lucky, because that job probably would have been taken for another 40 years. I know I’m not leaving anytime soon!

What exactly is your job?

I’m called Senior Scientific Assistant. What I do is basically the same as being a librarian. The fossils are in a kind of library. Every fossil has its place, and I can go find it. Researchers from all around the world come to study the fossils, and sometimes we loan them out. It works almost exactly like a library.

What’s your favorite part of your job?

It’s hard to answer, but I think one of my favorite things is identifying fossils for people. I’m the guy you would talk to if you found something in your backyard. It’s extremely entertaining and I love sharing with people what they found, whether it’s a real fossil or not.

One time a family came to me with a thing they found on a beach in Virginia. I freaked out! I immediately saw that it was the front part of a walrus skull. Since walruses only live in the Arctic now, that meant this was an ancient fossil. The family was so happy to see me so excited, they donated it to the museum.

What’s the best thing you personally have found in your adventures?

Probably the best thing I found was in Argentina, in 1997. I was with a friend, and we were looking for fossils of birds. We didn’t find any, but we did find lots of dinosaur eggs broken up all over the ground for miles. I began examining the eggs, and in about a hour I found an egg with a fossil of baby dinosaur skin inside it. This was the first time a paleontologist had ever seen a fossil of baby dinosaur skin, EVER! We found lots more baby dinosaur fossils and even more skin at this site.

What kind of baby dinosaurs were they?

Sauropods, the long necked dinosaurs.

Where else do your travels take you?

I am working on visiting and collecting fossils in every state of the USA and every continent in the world. So far, I have visited four continents and thirty-four states. Some states are harder than others. New Hampshire will be one of the hardest, because it’s mostly granite rock, and there are never fossils in granite.

What is your favorite thing at the American Museum of Natural History, for kids who might come for a visit?

We have a dinosaur mummy. It’s a hadrosaur, the duck-billed dinosaur, and almost the entire body is covered with the fossilized skin. You can see the tiny scales and wrinkles that were in the skin when the animal was alive. Anything that is rare gets me excited, and a fossil of skin is extremely rare. Bones are more likely to fossilize because they are hard, but skin is soft and starts to break down as soon as an animal dies.

Why should kids grow up to be scientists?

The way I see it, science is the best way we have for getting close to the truth. We can see evidence in nature that shows us the truth of the world. It isn’t someone’s opinion.

Is it a fun job?

It’s extremely fun. You have to get used to saying “I don’t know,” and you have to be comfortable with change. You have to be ready for the story to change dramatically when new evidence is discovered. But that’s exciting and fun.

So, is being a scientist discovering new things every day?

If you’re lucky, every day! That’s the drive for a scientist: seeing how little we actually know about the world, and how much we could still discover. It’s thrilling, and you will always being running into something you’ve never seen before.

The history of life is about 3.8 billion years. Every living thing on Earth is designed to be recycled completely. There is a limited amount of material, so it has to keep getting recycled for life to go forward. This is what makes fossils so rare.

It is extremely hard to become a fossil. It may seem like we have a lot of fossils in museums, but it’s a tiny amount compared to the huge amount of time that life has been around on Earth.

Scientists have really only just begun to discover fossils, and amazing and unexpected discoveries are happening all the time. Recently, some fossils of the ancestors of turtles were found in China. Scientists were amazed to find that early turtles evolved a shell on their belly before they had a shell on their back. No one had ever guessed this before!